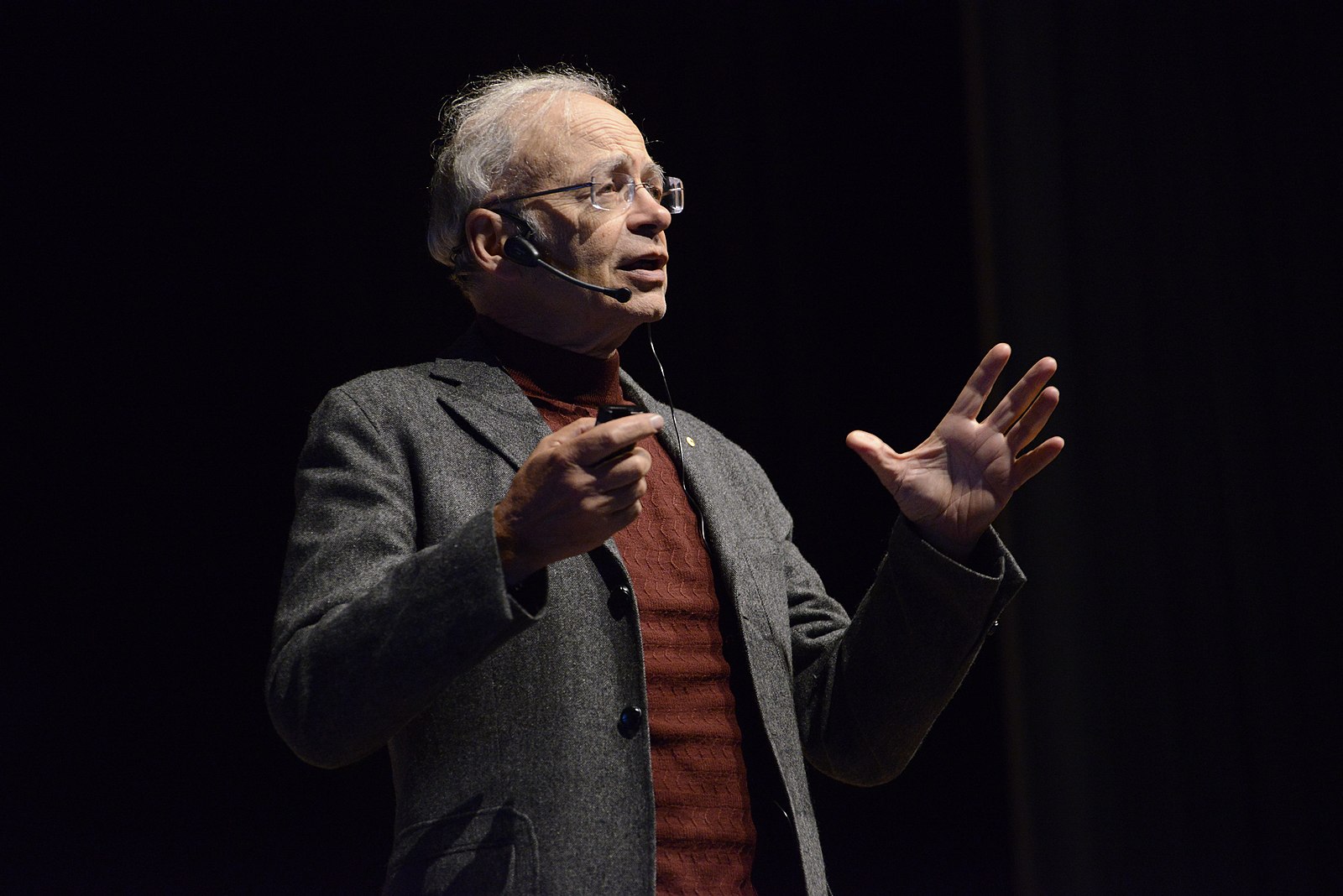

Peter Singer is Ira W. Decamp Professor of Bioethics in the University Center for Human Values at Princeton University. Often hailed as the world’s most influential living philosopher, Singer has authored a dozen books, including “Animal Liberation,” and most recently, “Why Vegan?”

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Harvard Political Review: Peter, you are known for popularizing the term “speciesism” in your book “Animal Liberation,” and you’ve been one of the greatest advocates for ending animal cruelty. In your view, what moral status should we assign to animals?

Peter Singer: We should assign the status of equal consideration of animals’ interests. But we need to be clear that when we’re talking about equal consideration of interests, we are talking about similar interests — we can only give equal consideration where we have similar interests. This doesn’t necessarily mean the interests of animals are the same as ours, and it may be that we have some interests that have greater weight than any comparable interest of animals, for example, interest in planning our life and living out our life over many years, which, I assume, non-human animals do not have the capacity to do. That may be an interest that will override any interest that animals have. But where we have similar interests, for example, the interest in not feeling physical pain — if we assume that there are similar amounts of physical pain being felt — then the status of animals should be one of equality.

HPR: You’ve chosen a utilitarian framework to advance your arguments against meat eating. Could you explain why you prefer a consequentialist approach rather than appeals to ethical duty or cultivation of virtues?

PS: I think the utilitarian view is the most straightforward ethical view. It deals with things that we’re all aware of — like the desire to avoid suffering or to enjoy pleasure. And that’s something that we can all see and understand. When we talk about duties or rights as the basis of morality — and I do think that we have duties and that beings have rights — I don’t think that that’s the foundation of morality. When we try to say that they are the foundation of morality, we’re talking about something a little bit more mysterious: where do these rights come from, which beings have them, what are the rights that we have. That all becomes very controversial and there seems to be no way of resolving that except by appeals to intuition. And people will have different intuitions on those matters. If we talk about virtue ethics — and I think virtues are important — it seems strange to make virtues the foundation of ethics because surely the point of virtuous behavior is that it does good for others and for oneself. And if the virtues did not do good, then we wouldn’t consider them virtues, so I think that you can’t really decide what is a virtue without having some other values that you’re trying to promote. That’s why I don’t think it makes a lot of sense to see virtues as the foundation of ethics.

HPR: How do you weigh concern for animal welfare in your utilitarian calculus, compared to say concerns for the environment?

PS: I don’t think that concerns for the environment are independent of concerns for the well-being of sentient beings. Ultimately, I don’t see the preservation of the environment as something of value if there were never to be any sentient beings affected by it. If somehow we could know that damaging the environment would not affect any sentient being — for instance, a last-person-on-earth scenario where you were the last person on earth and you thought it would be fun to burn down the forest on the island you’re living on before you die — I can’t see why that would be wrong. That would be a strange preference to have, but I don’t think it would be morally wrong. I think that these things really depend on the impact that they have on sentient beings to have moral significance.

HPR: You’ve previously said in an interview that you eat oysters and clams because you think they don’t have the capacity to suffer. I’m interested, then, in how you view the contentious field of plant neurobiology that seeks to establish plants as sentient beings with consciousness, albeit of a different nature from ours — leading some to argue that eating plants, or oysters for that matter, is just a more subtle manifestation of “speciesism” that you ardently condemn. How would you respond to that?

PS: I have not seen convincing evidence that plants are conscious beings. The word “sentient” is a little misleading, although it’s true that I use it and it is in popular use. But, strictly speaking, I suppose you can say, well, plants are sentient because they sense the sunlight and they turn their leaves towards the sun. That’s enough to be sentient. And in that sense an elevator door which senses whether you’ve got your arm in the way and pulls back if you have is also sentient. But I’m concerned about consciousness — about beings having experiences. There is a lot of intriguing information about plants, but to my understanding, none of it really establishes that plants have conscious experiences. Now, you could say, well suppose that we have information that they possibly do have consciousness. Then things would certainly change. We would want to avoid causing them suffering as much as we could, but we still have to eat something, and I don’t think starving ourselves to death and becoming extinct would be the right course of action to take. So we would then think about minimizing the amount of harm that we are causing to plants if we now think of them as having conscious experiences. And certainly that would still, I think, suggest that we ought to eat plants directly rather than consuming animals because animals eat far more of them. And if we eat animals, we are responsible for a vastly larger number of plants that were consumed. So that would still be a bad thing to do.

HPR: Would you urge vegetarians to go a step farther and embrace veganism?

PS: I think being largely vegan is certainly the right thing to do. It means that you’re not complicit in various forms of animal suffering and that you are eating a diet that is more sustainable for the planet. So yes, there are certainly reasons for doing that, but I don’t think it’s important to be a hundred percent vegan. You mentioned eating oysters and clams. That seems to me to be something that’s clearly not vegan, but I don’t see anything wrong with it if I’m right that oysters and clams are not sentient beings and if they are grown and harvested in a way that does not harm the environment. And there may be other cases too. If you eat cellular meat or cultured meat, then you would not be vegan, but I don’t see anything wrong with that. There’s no sentient animal being harmed, and it’s likely to be highly sustainable. So I don’t think it’s a matter of purity in being vegan. I think it’s a matter of avoiding animal products that either cause suffering to animals or are harmful to the environment.

HPR: Rather than hoping for a moral awakening in the hearts of people around the world, do you think it’s more worthwhile to focus on perfecting plant-based meat substitutes or lab-grown meat that will make relinquishing meat more convenient for future generations?

PS: I think we should be doing both. It’s really important to try to develop plant-based and cellular meat because that has the potential to dramatically reduce animal suffering and emission of greenhouse gases. That is something we should be doing, but I also think it’s important that people understand the ethical reasons for doing that. Otherwise, there may be other forms of cruelty to animals outside of consumption which we won’t make progress on. And I would like to see us making progress on reducing the suffering of animals across the board, even though I recognize that raising them for food involves by far the largest number of animals and is responsible for by far the greatest amount of suffering of any single activity involving animals.

Image Credit: Photo by Fronteiras do Pensamento is licensed for use under CC BY 2.0.