In September 2022, a 22 year old Iranian woman, Mahsa Amini, died in police custody after the morality police, an Iranian organization that enforces modest dress for Iranian women, detained her for not covering her hair with a hijab according to their regulations. While the morality police claimed Amini died of a heart attack, the circumstances of her death raised suspicion that the security forces had brutally killed her.

Amini’s death galvanized protests across Iran: Brave Iranian women are standing up against the Islamic Republic by refusing to wear the mandatory hijab, even as authorities have violently cracked down against protesters. The Islamic Republic recently made its first concession by abolishing the morality police, but protesters continue to advocate for an end to authoritarian theocratic rule. Protestors seek to end the dictatorship of Ali Khamenei, a government that holds a fundamentalist view of Islamic law and has enacted oppressive policies towards women and religious minorities.

As protests persist, Americans look on from across the globe and wrestle with the problem of their country’s obligations to the Iranians fighting for human rights and democracy — the very ideals America claims as foundational to its identity. The U.S. should not be appeased by the abolition of the morality police, which was a thinly veiled attempt by the Iranian state to divert attention from recent atrocities, such as its executions of protestors. Based on the United States’ status as the “leader of the free world” and its need to rectify historical wrongdoings in the region, demonstrated by the coup of 1954 and the exploitation of Iranian oil, its policy makers have a responsibility to support protestors. To avoid repeating the mistakes of past policies, however, the U.S. must do so through non-military actions.

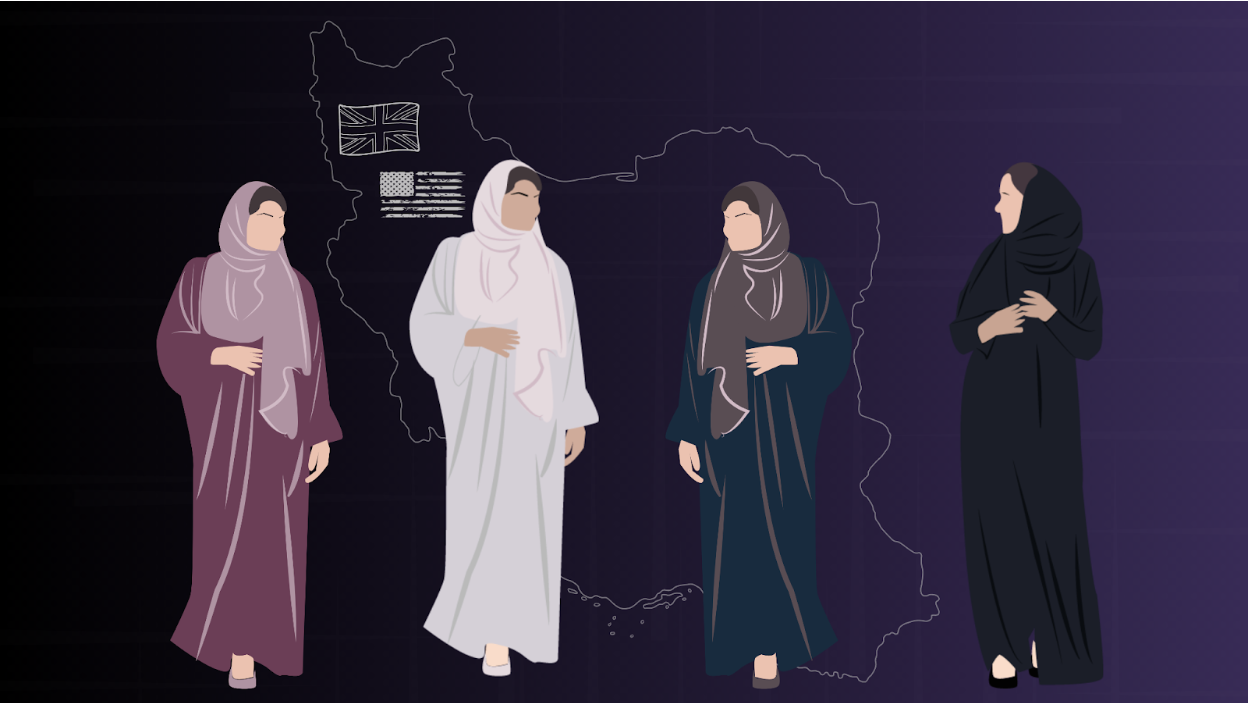

The United States has a shameful legacy in Iran, one that is deeply intertwined with Britain’s historical role in the country. In the early 19th century, Britain exerted the power of its “informal empire” over Iran through British shareholders’ majority stake in the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (now British Petroleum). This company, mainly owned by the British government, strengthened British economic control in the region, as it extracted Iran’s most valuable resource for profit. In the Post World War II era, the balance of global power shifted in favor of America. The U.S. usurped Britain’s former hegemonic status, but maintained a “special relationship” with Britain over a purported shared commitment to promote democracy globally.

However, contrary to the ideals of the Atlantic Charter, this “special relationship” led the U.S. and Britain to undermine foreign democracy. In 1951, the democratically elected Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh moved to nationalize Iranian oil and expel the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. During a period of Cold War hysteria, this decision provoked fears from the Anglo-American camp about the encroachment of Communist ideology in the region and anger over the threat to their business interests. Britain appealed to the U.S. for help in protecting their shared interests. The appeal succeeded: In 1953, the U.S. led a coup to overthrow Mosaddegh, a plan dubbed “Operation Ajax.” Through this scheme, the U.S. worked with Britain to subvert Iranian democracy by restoring the Shah, a puppet for Anglo-American commercial interests and a bulwark against communism.

In October of 1954, the Shah’s government agreed to allow a group of mainly U.S. based companies to manage Iran’s oil industry. The post-1954 situation in Iran looked eerily similar to before Mossadegh took power, with the U.S. replacing Britain as the foreign extractive power. The U.S. used the British playbook of propping up foreign figureheads benign to their interests, imitating the British strategy of empire on the cheap.

The United States’ informal imperialism in Iran proved unsustainable amidst the fervor of late 20th century anti-imperialist nationalism. Adopting the British strategy of military intervention to instigate regime change primed the U.S. for future trouble.

The coup destabilized the region by replacing a democratically elected ruler with an unpopular dictator, the Shah. The Shah’s ties to Western interest sparked backlash from the public, and created the conditions for the anti-Shah and anti-Western rhetoric espoused by Islamic fundamentalist Ruhollah Khomeini to gain popularity. Tensions came to a head during the Iranian Revolution of 1979, when supporters of Khomeini overthrew the Shah and replaced him with a Khomeini-led theocracy that was both hostile to the U.S. and oppressive toward its people. Empire on the cheap, it turned out, came at a price.

Today, as the U.S. once again turns its focus to Iran, it must critically examine its historical wrongdoing in the region as it weighs its role in the protests. In an alternate reality where the U.S. did not intervene to oust Mosaddegh, Iran today might have a secular, democratic government. Instead, by propping up the Shah, the U.S. bred civil unrest and spurred a revolution that created the totalitarian theocracy which protestors are revolting against today.

Because of the U.S.’s unforgivable role in creating tyranny in Iran, it must be a part of the solution to the oppression today.

Learning from the devastating Anglo-American intervention in Iran, the U.S. should avoid military action today. While the U.S. and Britain intervened out of self interest in 1953, even an intervention to support protestors and promote human rights today would have a similarly negative outcome. In Iran, public opinion of the U.S. is incredibly poor due to enduring resentment toward the U.S.’s history of economic imperialism in the region and its causal role in the coup that overthrew Mosaddegh. Iranians may view U.S. military intervention in support of protesters as another selfish American plot rather than a rally for freedom.

We do not need to look as far back as 1953 for reasons to avoid military intervention in Iran; recent American action in Iran’s neighboring countries, such as Afghanistan, has proven that the U.S. cannot bring regime change by force. In August 2021, the U.S. withdrew from Afghanistan after maintaining a military presence for nearly 20 years. The withdrawal caused a refugee crisis and the Taliban, an oppressive theocracy even worse than that in Iran, to regain control.

Iran is also a major player in geopolitics and on the verge of acquiring nuclear weapons. An intervention attempting to overthrow the Islamic Republic and insert a more liberal government — which America’s history in Afghanistan proves is likely to fail — would jeopardize the U.S.’s efforts to contain the nuclear threat that Iran poses. American intervention today could be far worse than the 1953 coup. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee Resolution in Support of Anti-Regime Protests in Iran recognized that the U.S. must take measures to help, while refraining from military action to attempt regime change. The resolution, passed two days after the Iranian government claimed to abolish its morality police, recognizes that the U.S. must do more than make inadequate concessions to ensure full freedom for Iranians.

The resolution also correctly emphasizes the need for the U.S. government to provide additional support for Iranians’ access to internet freedom. The resolution “supports internet freedom programs that circumvent the regime, including the Open Technology Fund, which provides support for VPNs and 21 other alternatives that can be used to bypass attempts by authoritarian governments to censor internet access during times of protest.” This would help protesters continue to use social media to share the police brutality they face, an activity the Iranian government is currently trying to censor through nightly app outages, disrupting V.P.N.s, and attempting to ban social media apps.

The resolution also recommends additional coordinated sanctions against the Iranian regime. This is questionable for several reasons, however. Though the philosophy behind sanctions is admirable — putting economic pressure on the regime to hold the region accountable and force liberalization — unintended consequences may ensue. Many members of the Iranian diaspora question the efficacy of sanctions, noting that when misapplied they can increase the state’s power by emboldening hardliners. The Iranian people would likely view any sanctions with suspicion because of the U.S.’s history of self-interested policy compounded by a widespread Iranian feeling of resentment towards American sanctions which have stifled the Iranian economy. Thus, sanctions may turn public opinion against the West and in favor of the Iranian state. U.S. policymakers must recognize the ways in which America’s past wrongdoing has tied its hands in current Iranian policy.

The U.S., in adopting Britain’s position as the global hegemon, also adopted Britain’s hubristic and greedy policies. Now, as Iranians protest this tyranny, U.S. policy makers must support them without falling into the trap of direct intervention. The U.S. should continue to amplify protesters’ voices by expanding their access to internet freedom. Beyond this, I do not see any easy way to help the protestors. I can only implore that U.S. policymakers first throw out the worn out, hand-me-down imperial playbook and affirm protestors by listening to their perspectives before taking action.