Aryaana Khan has spent much of her life rocked by climate disasters. In her home country of Bangladesh — a quarter of which is now underwater — the now-19-year-old student faced routine flooding and cyclones, disasters which only seemed to increase in number and intensity over the years, eventually forcing her family to immigrate to New York City. She lived in New York only one year before facing Hurricane Irene in 2011. A year after that, Hurricane Sandy tore through her community, leaving subways boarded up and schools cancelled in its wake. It was then that she started to see a pattern.

“I didn’t know that there was flooding every year and all of these cyclones because of climate change until I moved to New York in 2010,” she said. It was in New York that Khan connected the dots between these extreme events and climate change, learning that the disasters that forced her to leave her country and miss school days in her new home would only grow in intensity as global warming progresses.

Khan is only one of millions of Bangladeshi immigrants who have been displaced, many for the same reason as her family: to escape climate disasters. Only in 2016, extreme climate disasters forced 23.5 million people in Bangladesh out of their homes, many of them fleeing the severe cyclones that continue to befall the country. The Environmental Justice Foundation has estimated that by 2050, one in every seven people in Bangladesh will have been displaced by climate change.

For Khan, this brings a fear for the loss of a cultural identity at the hands of a rapidly warming planet. “Our identity is very intertwined with the land by generations of people going up and down as far as I know,” she said. “And when these things and these places go underwater, all of this other inheritance is going to go with it. Physically, when a place doesn’t exist, a lot of things get erased.”

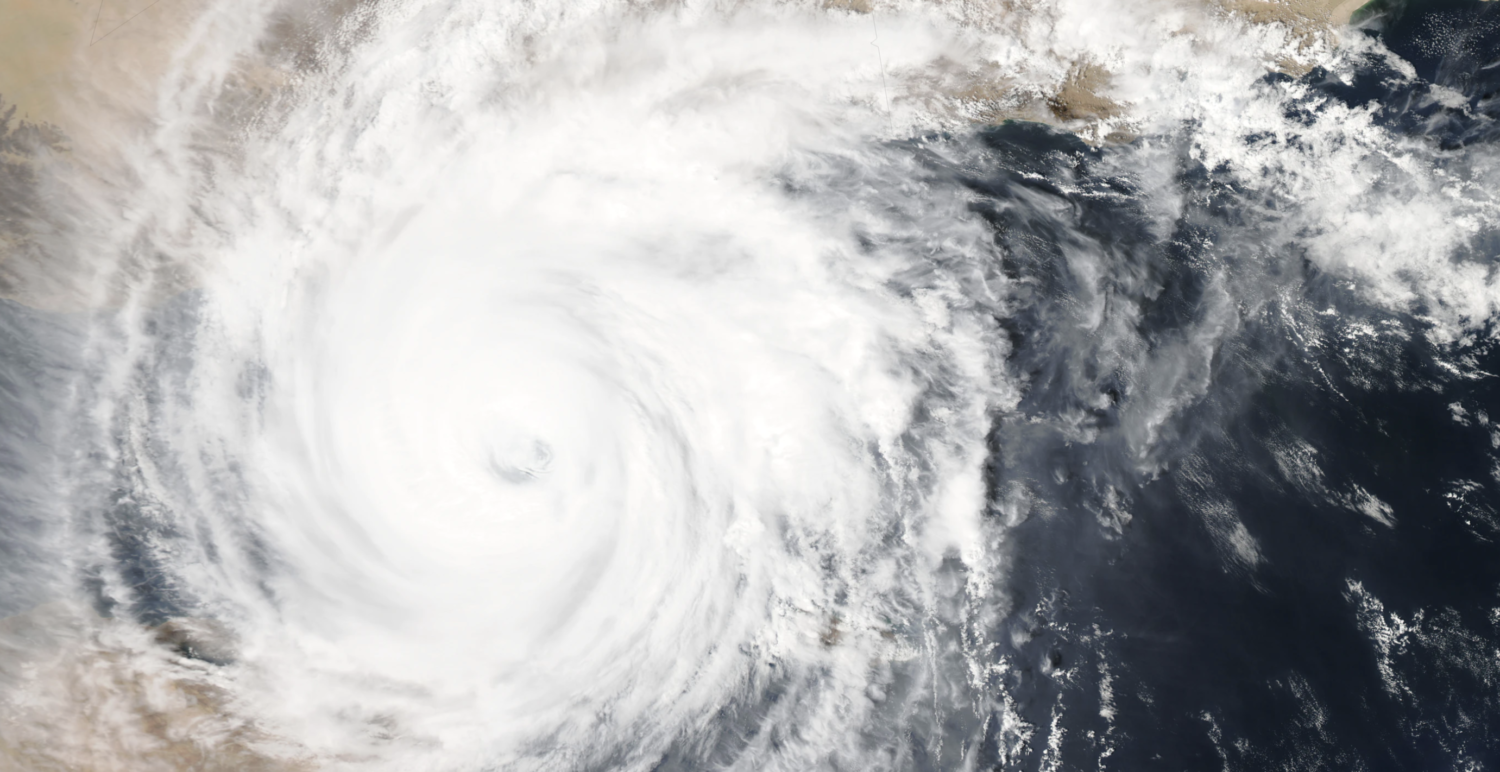

With the progression of climate change, disasters like the ones Khan experienced have only become more prevalent. Already, 2020 has brought with it an above-average number of storms with winds of 39 mph or higher in the Atlantic Ocean — including hurricanes and tropical storms. While on average there are 12 storms expected each year, predictions for this hurricane season rose to 13 to 19 named storms, six to 10 of which are poised to become hurricanes.

Though more named storms does not necessarily correlate with a greater chance of landfall for these storms, it does increase the overall odds of a storm making landfall — and thus the chance for it to cause widespread destruction. While major storms are incredibly harmful to everyone in their path, they are especially dangerous for communities that are already marginalized.

Hurricanes and Climate Change

Hurricanes form when changes in humidity, temperature, and pressure create a disturbance in the atmosphere, which then coincides with ocean temperatures of around 80 degrees Fahrenheit to create a “tropical system.” Favorable conditions such as increased humidity and constant winds fuel the system, helping it build and gain power. If wind speeds reach 74 mph, the system becomes a Category 1 hurricane, and if the conditions are right, winds can speed up to 157 mph or higher and cause devastating destruction to the communities that lie in its path.

During this hurricane season, the increase in named storms has been attributed in part to warmer temperatures below the surface of the Atlantic, but scientists have observed a growing number of storms per season since the 1970s. This is partly due to rising ocean temperatures — in the past 50 years, Earth’s oceans have absorbed 93% of the increase in Earth’s energy caused by the continued use of greenhouse gasses, leading to a 0.1 degrees Celsius rise in ocean temperatures every decade since 1970. At the same time, warmer oceans mean there is a dearth of cold water to serve as a “brake” for hurricanes’ strength. Due to this convergence of factors, a study from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicted that tropical cyclones and hurricanes will continue to increase in intensity throughout the 21st century.

Tropical storms can also cause greater devastation when they are combined with higher sea levels — another consequence of climate change, both from melting ice caps and from the expansion of seawater as its temperature creeps up. In fact, sea levels have already risen 7 or 8 inches since 1900 and are projected to continue rising in the coming years. When a hurricane meets a higher water level, it has a greater opportunity to whip up water, pushing farther inland and causing greater destruction to coastal communities.

Climate Disasters’ Connections to Environmental Racism

When Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast of the United States in the summer of 2005, it wrought death and destruction upon New Orleans in the form of major floods, bringing 80% of the city underwater and most affecting the communities of color and low-income residents living in Louisiana’s “cancer alley,” where residents already dealt with the environmental consequences of numerous petrochemical plants. After Katrina, these predominantly Black communities suffered a longer road to recovery, greater rates of displacement, and a greater likelihood of struggling with mental health as a consequence of the storm. These communities also went unaided for longer before being cleaned up or rebuilt, if they ever received aid at all.

As demonstrated by Katrina, hurricanes disproportionately affect marginalized communities, such as Black, Native American, Latinx, and low-income communities. This is due to a convergence of factors, including the systemic economic inequities that leave these communities with less access to health care, disaster insurance, the resources needed for a safe evacuation, and a lack of robust, storm-proof, and modernized infrastructure resistant to flooding and hurricane-force winds.

During Hurricane Andrew, for example, which hit Florida and Louisiana the hardest, Black and non-Cuban Latinx people were less likely to receive adequate insurance settlements for their losses than White residents. In fact, a 2019 study found that Black and Latinx residents in American counties that experienced $10 billion in damages from natural disasters like hurricanes between 1999 and 2013 lost an average of $27,000 and $29,000, respectively. White people in counties with similar losses due to natural disasters instead gained an average of $126,000.

“Environmental hazards — like environmental pollution, toxic pollution, bad water quality, impacts from a hurricane or another extreme event — are not distributed equally,” said Juan Declet-Barreto, a researcher with the Union of Concerned Scientists studying the disproportionate impact that climate disasters and other environmental factors have on communities of color. Among those facing outsize impacts, Declet-Barreto included undocumented immigrants, whose status often precludes them from accessing crucial resources to deal with the health-related and financial consequences of a hurricane.

Fernando Ramirez, a Puerto Rican student and the co-founder of Youth Climate Strike’s Puerto Rico chapter, experienced these inequities firsthand after the fatal Hurricane Maria in 2017. Living in Trujillo Alto, just 15 minutes from Puerto Rico’s affluent, majority-White capital of San Juan, Ramirez benefitted from a faster recovery rate after the storm than the rest of the island. While Ramirez’s power and water were restored a month after Maria, it took most of the island six months to get their utilities back. Many were also forcibly displaced by flooding or damage to their houses, moving instead to overcrowded shelters in search of refuge. In addition, a food shortage in the island meant many Puerto Ricans in rural areas also feared going hungry.

“The most marginalized communities had to suffer through a whole lot more than I did,” Ramirez said, adding how Loíza, the largest Black community in Puerto Rico, received virtually no help from either the island’s government or the federal government. Instead, much of the rebuilding of these marginalized communities came at the expense of the communities themselves, adding yet another burden on top of the hurricane’s massive destruction.

The present moment raises new concerns about compounding inequalities. Climate disaster from hurricanes will only exacerbate existing inequalities in communities that are already facing severe crises — from the coronavirus pandemic to the problem of police violence highlighted by the recent Black Lives Matter protests.

The Path Forward

Because of the human-driven reality of climate change, hurricanes will only become stronger and more frequent with each new hurricane season. This will lead not only to astronomical financial costs to the areas rocked by these climate disasters, but also to more insidious consequences for the people living within the path of the storms, consequences including but not limited to PTSD and other mental health issues, loss of property, loss of life, and forced displacement. Though hurricanes’ damage will be far-reaching, it will be felt most by the communities most vulnerable to their destruction: lower-income communities and communities of color, communities that are already more susceptible to environmental hazards and have resources to combat their effects.

Declet-Barreto says it is imperative that the United States take more seriously the risks posed by hurricanes. “We need to urge Congress to adequately fund and allow federal agencies to function and do the job … starting with the Environmental Protection Agency,” he said, adding that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Weather Service, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration should also receive additional funding.

But even if individual countries — beyond just the United States — manage to start implementing effective policies to mitigate climate change, there will still be climate refugees and a need to devote special attention and allocate greater resources to the most vulnerable. “Those are the populations that have been already dealing with the impacts of climate change and have been doing so in an inequitable way,” said Declet-Barreto.

For Aryaana Khan, that worst-case scenario became reality when she and her family felt they had to leave their home in Bangladesh. “It’s kind of wild that when you ask the question of why you left, you realize that, actually, leaving is not a choice,” she said. “And then you are a refugee. And there will be more, many more.”

Photo by NASA is licensed under the Unsplash License.