Natural disasters. Plagiarism scandals. Russian disinformation. The chaotic 2021 German federal election campaign could almost be mistaken for a U.S. presidential campaign. However, there is one major difference: the undeniable presence of an ascendant Green party that is ready to govern in Germany and Europe.

On Sept. 26, German voters will elect the successor to Angela Merkel. Merkel, who has served as Chancellor of Germany since 2005, has been adored by Germans for years. Her nickname, Mutti, is a German term of endearment meaning “mother.” Nearly 16 years after Merkel first assumed power, voters are going to the polls in a world dramatically altered by the coronavirus pandemic and the climate crisis. With their longtime chancellor heading into retirement, there is evidence that Germans are seeking change.

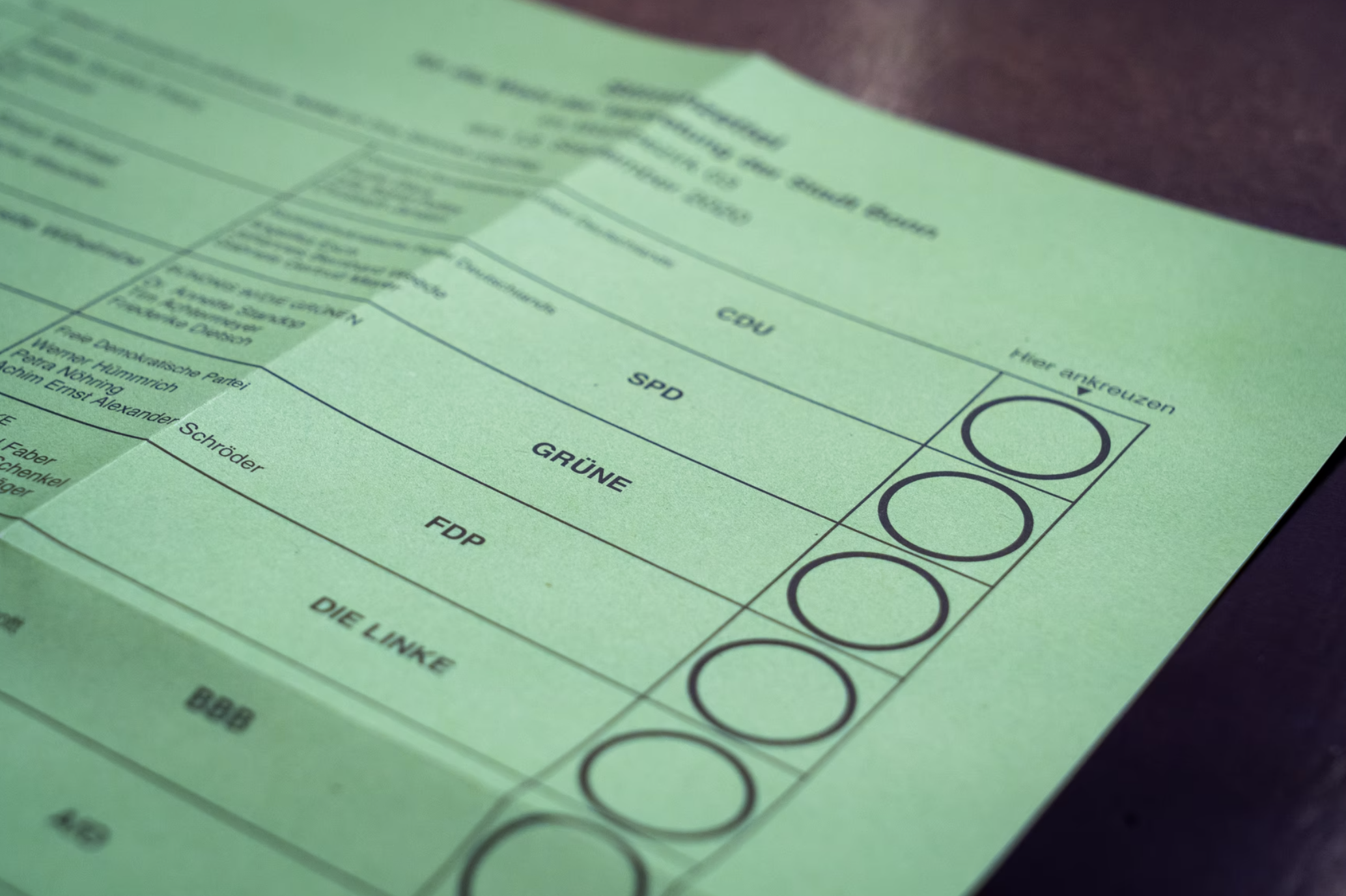

In April 2021, the Greens’ young, 40-year-old candidate Annalena Baerbock looked positioned to potentially replace Merkel as chancellor of Germany as the party reached first place in some polls. More recently, the Greens have been polling at third place, but they have nevertheless cemented their status as one of three major political parties in the country, alongside the conservative union party made up of the Christian Democratic Union of Germany and the Christian Social Union in Bavaria, also known as the CDU/CSU, and the Social Democratic Party, known as the SPD.

“The Greens are playing a key role in the radical change the German party system is undergoing at the moment,” explained Dr. Stefan Leifert, Munich bureau chief for Germany’s national public broadcasting station, ZDF. In an interview with the HPR, he said that the era of German politics when the CDU/CSU and SPD consistently won 40% to 50% is over. “Probably never again a German government consisting of just two parties can ever be formed again.” Leifert added, “This will give the Greens an almost equally important role as CDU and SPD.”

Now the Greens must convince German voters that they are more than just a party of activists shouting slogans. The Greens are eager to prove they can walk the talk by governing and enacting transformative legislation. Every indication shows they are prepared to do so.

Ready to Govern

The Greens have been shut out of the German federal government since Merkel became chancellor in 2005, and they are anxious to return to power. The first time the Greens were part of a government coalition was in 1998 when they had three ministers in Chancellor Gerhard Schröder’s cabinet. Due to the lack of governing experience, some argue that the Greens are not ready to take on a prominent role in a coalition.

Leifert disagrees, pointing to the Greens’ experience in the country’s various regional governments as to why they are ready to lead on a federal level. “On the level of the 16 German states, the Greens are part of the governments in most of them, including in Baden-Württemberg where they even lead the government,” Leifert said. Indeed, the Greens are part of the governing coalition in 10 German states behind only the SPD and the CDU/CSU, which govern in eleven states. By asserting their dominance on the regional level and gaining experience leading state governments, the Greens have proven that they are prepared to lead on the national stage. “In case it comes to a coalition with participation of the Greens in Berlin, I would expect them to come up with a well-prepared and experienced team of politicians,” said Leifert.

Critics frequently attack the Greens as a party solely obsessed with climate change and criticize the party as unable to govern when it comes to economic policy and foreign affairs. Annalena Baerbock and her party have worked overtime to change that image. The Green party manifesto released ahead of the 2021 election campaign is over 200 pages long and details every aspect of the Greens’ ambitious agenda, from fiscal policy to reforming the United Nations. A chapter about foreign policy includes entire paragraphs devoted to the Greens’ stance regarding the United States, Russia, Turkey, and China.

Rasmus Andresen, a member of the European Parliament from Germany representing the Greens, spoke to the HPR from Strasbourg, where he was attending a plenary session of the European Parliament. During the call, he was just as eager to talk about the dangers posed by Big Tech as he was to discuss the climate crisis.

Indeed, Andresen attributed his party’s success to its focus on tackling the major crises plaguing the world. “Things are changing in more conservative places like Germany because many people can see the big challenges lying ahead of us: tackling the fight against global warming, social inequalities, and other issues like gender inequality and racism.”

The Greens also have the flexibility to take on different roles depending on the coalition that is built. In a coalition with the presence of the Left Party, the Greens would work more closely with establishment parties to provide the government with stability. In a coalition with the CDU/CSU or the SPD, the Greens could take on a more familiar activist role pressing the parties to be bolder on climate change.

Although the Greens are not limited to activism, activists still play a central role in their coalition. One of the most complicated issues that the Greens will have to contend with if they succeed in returning to power is maintaining the support of their overwhelmingly youthful, activism-oriented, anti-establishment voter base. Andresen insisted that any concessions his party makes during coalition talks must consider the activist groups that support the Greens. “We will need to strengthen the ties and the alliance we have with some of the youth movements, but also others in civil society,” said Andresen. “We need to have a close relationship with them, communicate with them, and discuss our compromises with them.”

Those activist groups and protest movements deserve credit if the Greens succeed in pushing the SPD or the CDU/CSU to accept their more ambitious climate change and social equality agenda. Andresen believes that the support of the German electorate is indispensable. “If there is no pressure coming from the street, then there will be no balance in the political debate.”

More than a German Election

The result of Germany’s election will have consequences that extend far beyond national borders. German voters will be electing the leader of the largest nation in the European Union. In the EU, where the heads of state and government wield significant power as the European Council, everyone will be paying very close attention to the results of Sunday’s vote.

In addition to her official job as the German head of government, many also viewed Merkel as the unofficial leader of Europe. A recent poll by the European Council on Foreign Relations found that a plurality of Europeans would pick Merkel to lead the European Union over French President Emmanuel Macron. The absence of Merkel’s leadership skills will be missed at European Council summits, where she was instrumental in helping leaders reach unanimous agreements. Her successor will have very large shoes to fill, both in Berlin and in Brussels.

The EU might not find its next leader in this election, but it will gain a staunch defender and supporter. “If you are looking at the three top Chancellor candidates … you can see that all of them, in a way, want to strengthen Europe,” Andresen said. “It is not like any of them are anti-European or against the European Union. That is not the case.”

While recognizing that the two other major parties are pro-EU, the Greens have attempted to distinguish themselves as the political party of the European Union. One of their major policy stances is advocating for a transfer of power from member states to the EU.

“On climate, the European Union does not have enough power to act like how it is needed to act. You can look at the Paris Agreement as one example,” Andresen said. “We think we need to do more fighting Big Tech, where we would like to see the European Union come up with strengthened laws fighting Google, Facebook, and others.”

The Greens are prepared to take their bold plans for change straight to the Reichstag and the European Council. Despite being open to compromise on some issues, they are also prepared to push back strongly on others, especially on climate.

During a televised debate between the chancellor candidates for the SPD, CDU/CSU and the Greens, SPD candidate Olaf Scholz insisted that he would resist quick and costly climate change proposals. “We want to go the moderate way,” Scholz said. Green party politicians insisted it was proof that a vote for the SPD would be a vote for more of the same.

“It is simply not enough,” Andresen said of the SPD’s climate agenda. “We need to see some more action.”

Image Credit: Image by Mika Baumeister is licensed under Unsplash License