Everyone in the generations before me remembers where they were on 9/11. For me, an equally seminal moment was Barack Obama’s inauguration. Even in ruby red Texas, my third grade class excitedly gathered around the television to watch the United States’ first Black president take the oath of office. At the time, none of us realized what the next eight years would bring; we only squirmed in our seats as the ceremony ate away at our recess time.

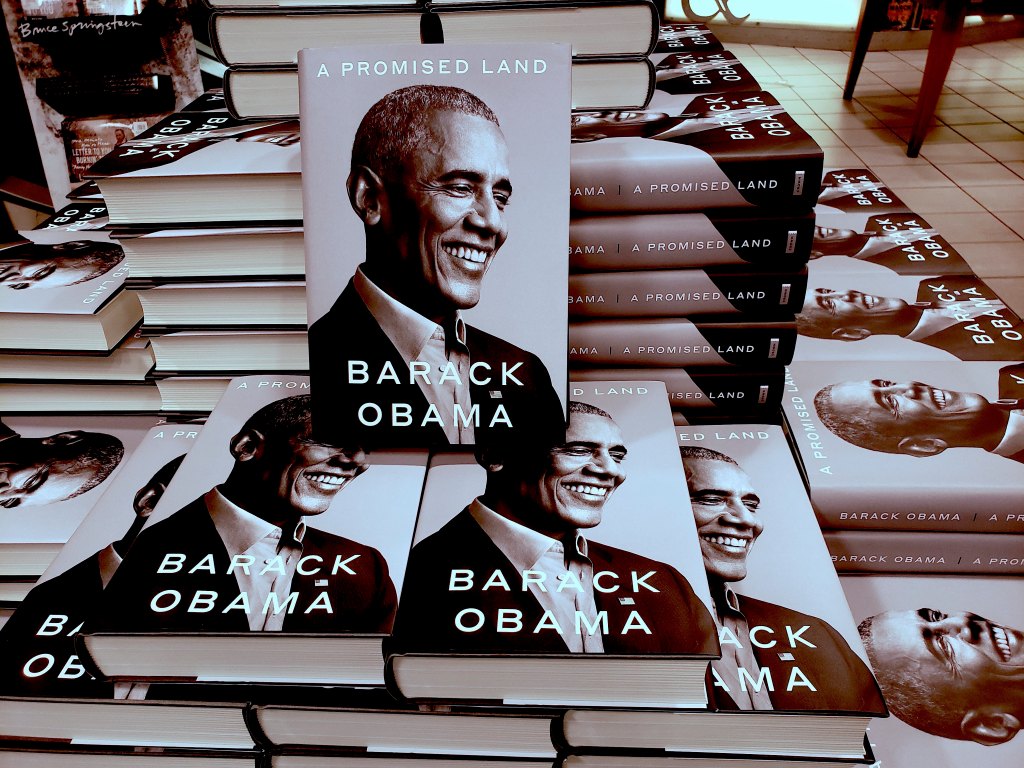

Reading the inaugural portions of Obama’s new memoir, “A Promised Land,” I thought back to that moment in third grade and realized how much our politics has changed since. The book is a particularly potent reminder of that shift, especially since Obama sets out to explain his presidency’s key decisions with an eye towards clarifying those decisions for future readers and historians. More than that, though, Obama hopes to humanize the office, to “give a sense of what it’s like to be the president of the United States.” He unequivocally succeeds in both those goals: “A Promised Land” offers an inside look at both his presidency’s momentous occasions and its greatest defeats. Beyond that, though, “A Promised Land” is a profoundly useful historical document, written with a clear eye towards preserving Obama’s legacy in the historical record.

Obama begins with a brief overview of his political career, picking up more heavily in 2007 with the story of his presidential campaign. Subsequent chapters deal with the major issues of his term as he saw them: the economy, wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and healthcare. As he grew into the presidency and made progress on many of his major initiatives, he details how his administration dealt with crises as they popped up: the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, Greece’s debt crisis, and the Democrats’ drubbing in the 2010 midterms all get significant treatment.

Structurally, the book does not proceed along strictly chronological lines. After all, Obama points out that “A president has no choice but to continually multitask,” so he instead adopts an issue-by-issue framework. This framework allows us to grasp the contours of one particular issue more easily without having to constantly switch focus. Because the book moves at a brisk pace, though, this semi-chronological structure presents a problem: It assumes readers already have a good grasp of the timeline involved. Amidst a 700-page tome, however, I lost my sense of how the different topical issues fit together, especially since the book contained very few orienting dates.

The book concludes with Obama recounting the process that ended in the death of al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden. Although Obama brings valuable insight about the decisions he and his staff made leading up to that fateful raid, the book terminates rather abruptly. Even though he employs otherwise easily recognizable transitions, Obama doesn’t leave me with a sense of where the following book may be headed, nor does he justify his choice of the bin Laden raid to bifurcate his two memoirs. I wonder why he chooses not to divide it more clearly between the first and second terms of his presidency, or at least offer a quick preview of what is to come.

Beyond those comparatively minor structural issues, the book shines for a mass-market audience. For starters, Obama is a consummate storyteller, making even dry policy discussions sound interesting. He often introduces important policy issues with engaging anecdotes; he segues into climate change by recounting his daughter Malia’s desire to save the tigers, for instance. Even though Obama occasionally gets into literary descriptors, these do not bog down the prose, which moves along at a rapid clip.

In terms of content, the book does not have any hallmarks of a bad presidential memoir. Craig Fehrman, who has written a book on presidential memoirs, told the New York Times that these accounts often “quickly derail amid policy wonkery, self-justification or score-settling.” “A Promised Land” does none of these things.

To begin, while Obama is a self-proclaimed policy wonk, he does not fall into the first trap. Even when he could dwell on the details of his team’s economic response or Obamacare, he does not. After all, we can easily consult other publicly available sources for more technical details regarding both issues and others. Instead, Obama offers a more candid account of the political negotiations that went into passing legislation and executing his administration’s agenda, providing unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the Obama White House. This insight adds clarity to the historical record, shedding light on incidents and actions that perhaps went unexplained in contemporaneous sources.

Obviously, Obama does engage in some self-justification. After all, explaining why a president makes the decisions that he does is an important feature of a presidential memoir. But responding to critics is not the book’s primary purpose, and he takes full responsibility whenever he commits an error or faux pas. When Obama receives the call informing him that he had won the Nobel Peace Prize, he is at his most humble: “For what?” he wonders. “Less than a year into my presidency, I didn’t feel that I deserved to be in the company of those transformative figures who had been honored in the past.”

Finally, Obama does not engage in significant score settling. Admittedly, he does take some shots at Republican obstructionists in Congress. He writes that Lindsey Graham always “seemed to find a reason to wriggle out” of previous commitments he had made, and Mitch McConnell used his “discipline, shrewdness, and shamelessness” in the “single-minded and dispassionate pursuit of power.” But even when he felt significant annoyance at Republican obstructionism or remarked on the birther movement led by one Donald Trump, he resists the temptation to go all out against them. We need an anger translator to make the book derisive.

In the aftermath of the insurrection on Capitol Hill, this calm and reasoned tone emphasizes the contrast between the Obama administration and the Trump administration. Trump devoted his entire administration to taking shots at his enemies; Obama spent his administration trying to pass legislation and gain Republican support, even if they would not vote for his proposals in the end. In all, “A Promised Land” succeeds not only in offering us a look inside the depths of the presidency, but in further distinguishing Obama’s years in office from Trump’s for the historical record. At this moment in time, the book reminds us what democracy has looked like, what it should look like, and what it can be again.