Despite the significant amount of aid seemingly invested in the Global South, intergenerational mobility (IGM) has largely stalled in low-income countries. According to a World Bank report evaluating the global distribution of economic mobility outcomes, developing economies comprise 46 of the bottom 50 economies in terms of upward mobility measures. This is a striking and counterintuitive reality: Though billions of dollars have been spent in an attempt to improve the national well-being of “developing nations,” many individuals in these countries are not earning at a higher income percentile than their parents. In short, economic well-being is not progressing across generations: Many individuals remain increasingly constrained by the socioeconomic circumstances of their birth.

Adverse intergenerational outcomes are particularly acute in Least Developed Countries (LDCs). These countries, which are characterized as those highly vulnerable to environmental and economic shocks, are disproportionately located in Africa and Southeast Asia and represent 38% of the world’s “extremely poor” population. Even with overall rising GDPs due to the advent of globalization and foreign aid, nearly half of the national population in LDCs consistently remain in extreme poverty.

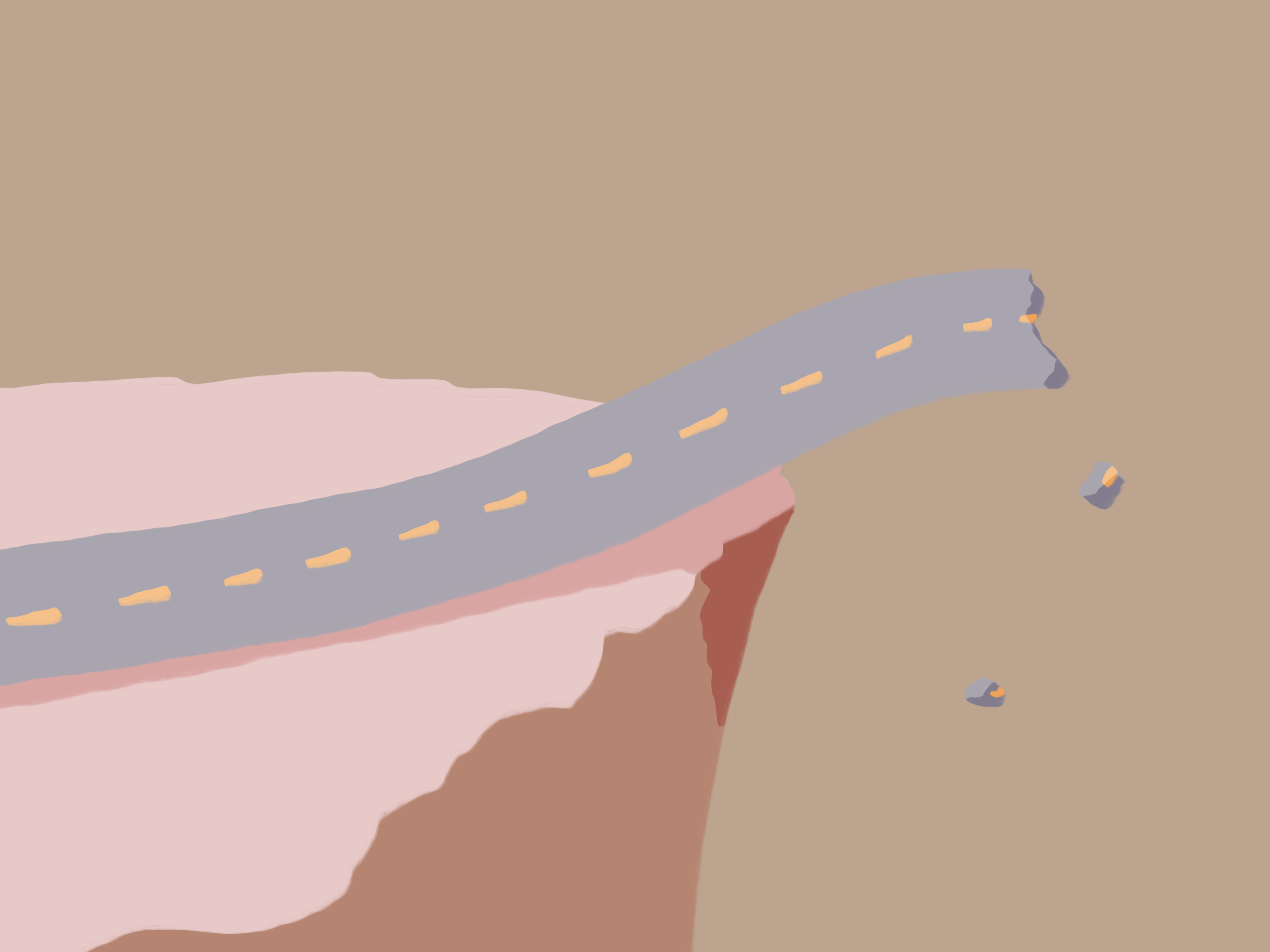

This is not a random phenomenon. Rather, the geopolitical self-interests of aid contributors have created funding gaps that have crippled upward mobility in the world’s poorest countries. This has enabled a recursive loop in which vulnerable countries are unable to improve over generations because of insufficient financing, causing them to continually require aid. The global distribution of foreign aid explains this trend: Even though the overall amount of aid has been steadily increasing, the proportion of that aid reaching Least Developed Countries has declined in parallel.

In 2019 alone, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, total foreign aid hit a record high of $152.8 billion. The United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom were the largest benefactors of this development assistance, together contributing more than half of the total global share. While funding priorities vary annually and depend on local contexts, they have consistently emphasized upgrading water and sanitation conditions, strengthening health infrastructure, and implementing education programs in order to build a robust national workforce. International development is a vast field with myriad purposes, but its core objective is ideally to create sustainable improvements in individual well-being across the world, enhancing human freedoms in the process.

However, foreign aid mechanisms are not exclusively driven by need: They necessarily reflect the interests of their patron countries. The share of funding to LDCs has decreased in favor of increased aid to middle-income countries, particularly those whose donor countries have vested interests in. For example, countries such as the United Kingdom, Austria, and Canada have consistently given higher aid to developing countries from which they import more. Similarly, proximity and migrant networks also correlate with higher aid received. For example, since the second Bush administration, the United States has emphasized giving a disproportionately high amount of aid to Central American countries, citing American security and well-being interests. Ultimately, such contributing factors mean that development assistance is not as inclusive of poor countries without existing relationships with donors as it ought to be. In a self-propagating cycle, this then excludes many LDCs from receiving their requisite amount of aid, freezing their citizens’ intergenerational mobility outcomes.

Intelligent funding decisions often do have the power to transform intergenerational mobility outcomes in developing countries, especially LDCs. The overall lack of improvement in this dimension for many developing economies can therefore be attributed to whether funding is actually given to countries that need it.

When invested thoughtfully, funding for social policies has tremendous potential to boost upward mobility outcomes. In the United States, research by Opportunity Insights illustrated the huge geographic disparities in social mobility across the country. For example, a child growing up in the bottom fifth of the income distribution in Charlotte, North Carolina has a 4.4 percent chance of earning in the top fifth of the income bracket, compared to a 12% chance for a child in San Jose, California. In response to such stark disparities in economic opportunity, researchers used federal tax data to investigate the impact of housing vouchers, which would allow families with young children to move to lower-poverty neighborhoods. The results were tremendous, showing that children under 13 who moved to a lower-poverty area earned approximately 31% more than children who did not. It follows that continued, targeted financial support of a housing voucher plan would dramatically equalize upward mobility outcomes.

This logic that directed funding improves intergenerational mobility holds true in the Global South as well. Empirical studies show that countries receiving a higher percentage of foreign aid against their total GDP have higher measures of upward intergenerational mobility, compared to countries receiving less foreign aid. Particularly, investment in educational programs was most effective in increasing upward mobility. For example, when projects across Africa increased the number of teachers per student in secondary schools, projections of upward mobility increased. In areas where the student-to-teacher ratio failed to improve, downward intergenerational mobility was much more likely.

In order for foreign aid to equitably improve upward mobility outcomes across the world, as it has demonstrated the potential to do so, we must cease thinking that giving foreign aid is an act of benevolent charity. Global wealth is concentrated in the Global North because of historically extractive economic systems, such as colonialism and imperialism. Therefore, foreign aid should aim to be distributed universally, where it is truly needed, in order to repair persisting inequalities — not where the donor country finds it most personally useful to invest. Only then will we see sustained upward mobility in developing countries, realizing our hopes of global progress.