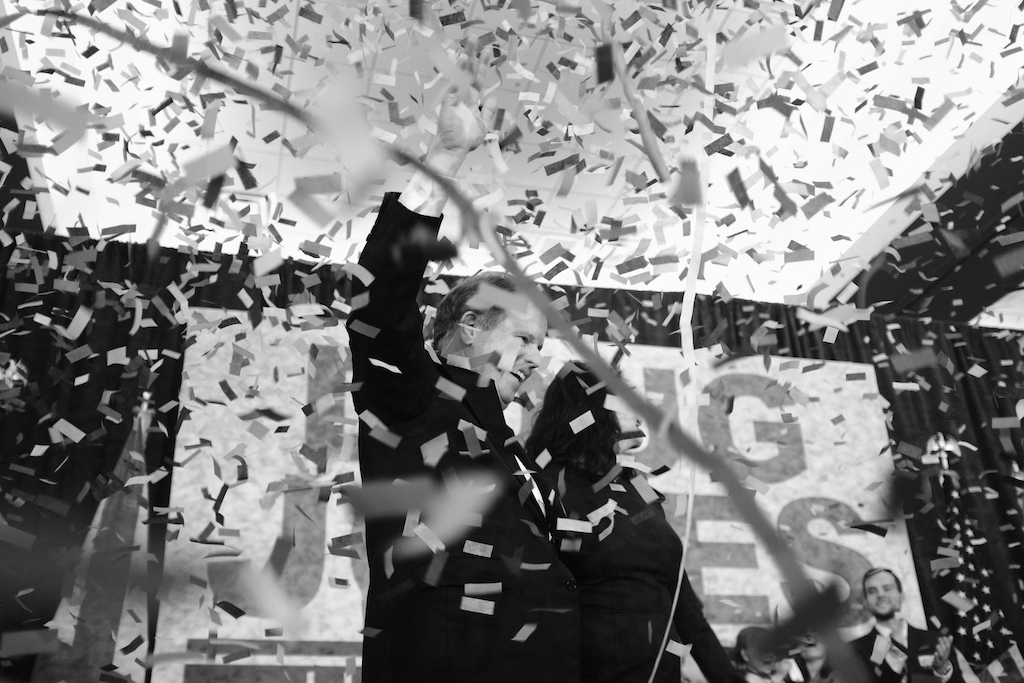

On one remarkable night in December, red, white, and blue confetti rained down on supporters of Senator-elect Doug Jones. The Birmingham Sheraton Hotel was filled with Democratic exuberance long absent from Alabama. Jones’ breathless victory couldn’t help but stand in stark contrast to the sobering images of unused “glass-ceiling” confetti from Hillary Clinton’s election night party. She lost Alabama by nearly 28 points—yet, just over a year later, Alabama elected its first Democratic Senator since 1992. The surprising victory has sparked hope among Democratic activists that even the American South—a bastion of Republican voters over the past 30 years—is in play during the 2018 and 2020 elections.

Many of those activists hope that Democrats can win on a steady diet of anti-Trump rhetoric and mainstream liberal ideas—a formula that Jones executed perfectly. President Donald Trump’s approval rating is hovering around record lows and, as Jones’ victory showed, it can significantly lower Republican and raise Democratic turnout. However, anti-Trump sentiment alone might not be enough to carry the Democrats in the 2018 and 2020 elections and beyond. Can Jones’ win be replicated beyond a Trump administration? A 50-state strategy more closely tailored to local politics could win Democrats crucial seats in their bid to regain control of the House, Senate, gubernatorial offices, and state legislatures. In addition to the national party’s focus on local organizing, individual candidates can do a better job of representing their specific constituents’ ideals and policies. By focusing on the mantra “all politics is local,” Democrats can win in a broader geographical region than their national policy would otherwise allow.

What does Doug Jones’ Victory Mean?

Although Jones’ victory sparked hope within the Democratic party, it’s hard to tell how predictive his victory is for future elections in the South. Can Democrats simply win off of backlash to the Trump administration? To answer that question, we must first determine how much of Jones’ win was attributable to his opponent, accused child molester Roy Moore, and not anti-Trump sentiment. Using a post-election breakdown formulated by modelers at FiveThirtyEight, we can see if the results from Alabama represent a winning formula or an outlier that could lead to complacency.

Usually a 28- or 29-point Republican stronghold, Alabama fell to Jones by 1.5 points. This means that between Moore and Trump, we need to account for about 30 points of change. Polling indicated that Moore was 10 points worse than the average Republican candidate to start with, and allegations published by the Washington Post cost him another 10 points. That combination leaves 10 points of other impact which can be explained by the president’s lack of popularity, aligning nicely with Democrats’ 10-point margin on generic congressional ballots. The logical question is how much will a 10-point swing affect 2018 midterm elections? The short-term answer is that, especially in the South, a Trump presidency could significantly boost Democrats’ chances: a 10-point swing on the generic ballot would put almost 40 congressional seats into play. If by this November, Democrats still maintain a 10-point edge on the generic ballot, all 39 seats with a 10-point Republican edge or fewer should be competitive. Based on the Democrat’s last wave election in 2006, Democrats will only win around 65 percent of those seats. That math would mean Democrats could win 25 congressional seats in the South. Democrats only need a total of 24 seats nationwide to take back the House.

So, perhaps in 2018 and 2020, southern Democrats in relatively close seats can win. “This is going to be a weird, weird, weird year where anything can happen,” said Greta Carnes, a longtime Democratic organizer in the South, in a recent interview with the HPR. But what happens after that? A potential surge in popularity could be enough to take back the House but will not last if Democrats fail to adjust their strategy. Democratic leadership has acknowledged the need for new strategy and is actively working to shift their techniques nationwide to focus more on local organizing.

A 50-state Strategy

The Democratic National Committee has long-term hopes that Democrats can win in the South regardless of the president in office. Tom Perez, the DNC chair, has publicly advocated for the return of a 50-state strategy—a term and technique coined by former chair Howard Dean. This involves actively investing in state parties everywhere. It is meant to appeal to a broad base of Americans by being both localized and hyper-aggressive, never ceding any electoral ground unopposed. The strategy was largely credited with massive electoral victories in the 2006 and 2008 elections, handing Democrats seats in traditionally red states like Kansas and Montana.

For all its success, however, the 50-state strategy was seemingly abandoned in early 2009 when the newly elected president, Barack Obama, created Organizing for America. OFA regulated the DNC to a money pass-through for large donations while it advocated only for the president’s policies like the Affordable Care Act. Without a consistent grassroots effort on behalf of all Democrats, “[Democrats] started losing races all across the South,” Jaime Harrison, chair of the South Carolina Democratic Party and former candidate for DNC chair, told the HPR. “[Democrats] eventually lost the majority in the House. That majority was built on southern seats.”

After a sluggish 2017, the DNC has reaffirmed its commitment to state parties both in word and action. Starting under Perez’s leadership, each state party is granted $10,000 a month by the national party which has identified the most vulnerable Republican seats, including many in the South. Eight southern states have congressional districts targeted to be flipped by the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee. More are sure to follow. Harrison evoked a territorial battle by saying, “If the Republicans aren’t ceding territory, why the hell do we cede territory to them? We could win in places—Democrats have won in places like North Dakota and South Dakota and Montana.”

The more aggressive approach is partially enabled by the surge in declared Democratic candidates that has reached unprecedented levels across the South. In Texas, for example, for the first time in 25 years, Democrats will be running for all 36 congressional seats. The “no ground given” attitude of the national party seems to have extended to grassroots efforts as well. Not only are federal elections being challenged at remarkable rates, but, according to the Texas Democratic Party, Democrats are running in 89 percent of state house races and 88 percent of state senate races.

If Democrats can have an active presence in southern states and are able to field candidates for elections, the next challenge is actually turning out voters. Carnes underlined the challenge of voter turnout, explaining that “turnout is everything, especially in a midterm election.” And, although a dedicated local presence can drive turnout, what ultimately moves people to vote is the candidate, not the national party.

Southern politics, southern policy

Crafting a popular Democratic platform in the South is no easy task—and one that has caused a significant amount of consternation among activists. One proposal is to implement the national platform as outlined by the DNC. The second proposal is that Democrats in rural areas should move right on more ‘social’ issues like the gun laws and abortion. Both of these arguments have clear fallacies: the first dictates a single ideology for everyone, the second fails to stand firmly for progressive values. Brad Komar, the campaign manager of recently elected Virginia Governor Ralph Northam, told the HPR that “voters get to pick what matters most to them. It’s not parties, campaigns, or politicians.”

Luckily there is a middle ground. The DNC need neither dictate policy nor encourage the dilution of their message. Instead, Democrats can rely on the electoral free market, or the principle that constituents will elect good candidates that represent their values and policy ideas. To better encompass the values of their constituents, the Democratic party should shift to a ‘big tent’ ideology, welcoming in classic liberals, blue dogs, and whatever new coalitions or caucuses arise. Harrison expressed disgust towards the idea of litmus tests for Democrats: “We, as a national party, don’t control the constituents in South Carolina. We don’t control the citizens in North Dakota or Missouri. Those people, at the end of the day, are going to pick the man or woman or someone who reflects the things that are of their values.”

Because Southerners are not a monolithic group, they will elect a range of candidates. In other words there is no single, perfect southern candidate. Recently elected Virginia Governor Ralph Northam stands in sharp contrast to Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards. Although both are Democrats, Northam advocates gun reform while Edwards describes himself as pro-Second Amendment. Northam supports abortion rights while Edwards is staunchly anti-abortion. Both, however, are Democrats elected in the South because of what Komar calls “credibility.” By running as an authentic Virginian as opposed to being seen as a D.C. insider, Northam spoke to southern values while running an extremely liberal campaign. Edwards may be an even better lesson to Democrats however, as he was elected before the Trump administration.

By no means are either of these the only recipes for success. Democrats can run on a number of platforms, ranging from moderate to liberal, but Komar made one point abundantly clear: “credibility of a message is almost as important as the message itself.”

What does it all mean?

There seems to be a perfect storm brewing for Democrats in the South. The political environment right now is ripe for upsets and could lead to a wave election in this round of midterms. For sustained success, however, Democrats need to invest in their state parties. Much of that responsibility falls on the backs of candidates themselves, even with a more robust national organizing presence. Candidates can and should speak to issues on which they have credibility. Like Northam and Edwards showed, that will lead to different policy solutions. By focusing more on local organizing, candidates can craft policy platforms that speak to the beliefs of their constituents while upholding Democratic ideals. “You just can’t have all the answers for what’s ailing their communities,” Harrison expounded, “Sometimes, you know, that’s difficult for Democrats.”

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons/Jamelle Bouie