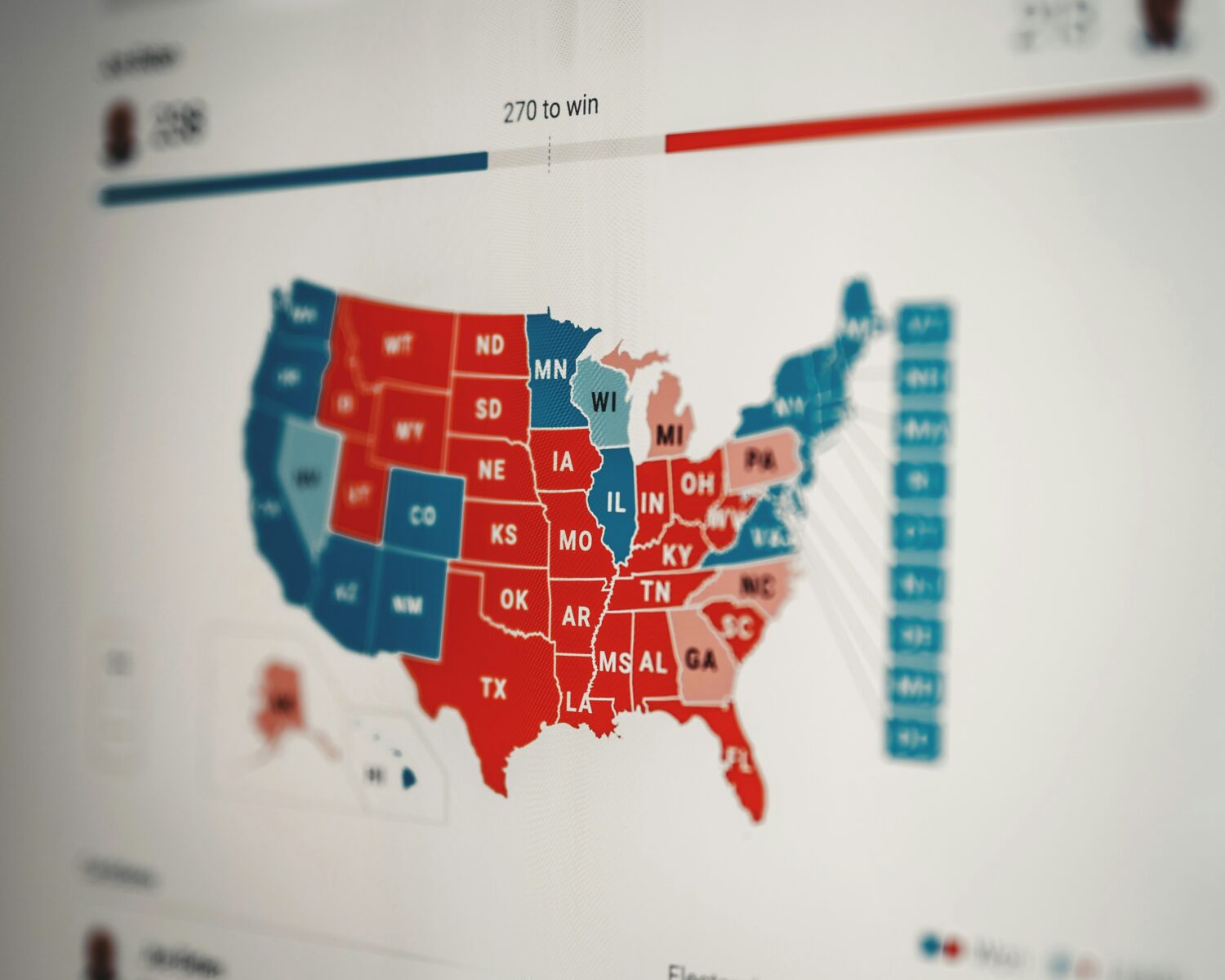

Do you live in Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, Arizona, Georgia, or Nevada? Great news! Your vote is incredibly important for the 2024 presidential election. Unfortunately, if you live anywhere else, your vote is practically meaningless when determining who will be inaugurated next January.

The Electoral College’s winner-take-all system has long been criticized for allowing candidates to focus on a few “swing states” while ignoring the rest of the country. In 2020, for example, six million Californians voted for former President Trump, the most votes a Republican has ever received in any state in any race since the country’s founding. Yet, all 55 of California’s electoral votes went to Joe Biden, a crucial element of his victory. Similar phenomena happen in nearly every “safe state”; only Nebraska and Maine have attempted to create more proportional systems by dividing their electoral votes by congressional district.

These inadequacies of the Electoral College are well-known by many Americans disheartened with their voice being ignored in presidential elections. A September Pew survey reported that approximately 65% of adults would prefer to change to a popular vote system — the highest level of support Pew has registered in the two decades it has tracked opinions on this reform.

Two main methods stand out when discussing reforms to the American electoral system, yet both are unlikely to ever come to fruition. The first is a constitutional amendment to replace the Electoral College with another system. Though most Americans might support this, attaining the necessary consensus for an amendment is daunting. This process requires a two-thirds majority in the House and Senate and ratification from three-fourths of state legislatures or state conventions. Further complicating this is the partisan nature of the issue; only 47% of Republican or Republican-leaning voters support such a change. This is expected given that more pollsters believe it is much more likely for a Republican candidate to lose the popular vote but win the Electoral College than the other way around. With Republicans controlling at least one legislative body in 33 states, passing such an amendment seems highly unlikely without a radical change in political opinion.

The other path would be for states to change their laws that use the winner-take-all system. Similarly, this runs into a few roadblocks. First, there remains a similar challenge of political will. States like California, with a dominant party, may be reluctant to change a system that has consistently worked in their favor if other states keep their winner-take-all system. Such a proposition only stands to lose the dominant party’s crucial electoral votes. Additionally, this change would require a level of nationwide coordination that has thus far not materialized. Each state independently decides its method of allocating electoral votes, making a unified approach difficult. Changes at the state level may not significantly affect the Electoral College’s balance unless many states, particularly those with numerous electoral votes, adopt these changes at once. Despite these challenges, this approach is more feasible than a constitutional amendment, though still extremely unlikely.

Against this backdrop, an innovative legislative proposal, the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, was introduced in 2006 as a feasible alternative mechanism for instituting a national popular vote system. The NPVIC operates on a simple premise: It requires participating states to allocate their electoral votes to the presidential candidate who wins the national popular vote, regardless of the state-level results. This approach ensures that the popular vote winner becomes president, bypassing the winner-take-all approach currently dominating most states’ systems. For example, even if Joe Biden won 65% of the vote in California, the state would still send all of its 55 electors to Donald Trump if he won the national popular vote. The NPVIC employs the concept of “faithless electors,” which refers to electors who cast their votes differently from their pledged candidate.

Such legislation that skirts around the original system for Presidential elections outlined in the Constitution may straddle the line of legality. However, the Supreme Court, back in July 2020, unanimously ruled that the Constitution provides a broad mandate for states to allocate their electors as they choose. In the majority opinion of Chiafalo v. Washington, Justice Kagan wrote, “Article II, section 1’s appointments power gives the States far-reaching authority over presidential electors, absent some other constitutional constraint. […] This Court has described that clause as ’conveying the broadest power of determination’ over who becomes an elector.”

The NPVIC also addresses concerns of states hesitant to alter their laws without similar actions by others. Embedded within the legislation is a clause stating that the compact only comes into effect once states collectively totaling 270 electoral votes — the number required to win the presidency — have joined, making it much simpler for states to join. Additionally, instead of requiring all 50 states to participate, there must simply be enough to accumulate 270 electoral votes. The assent of states like Wyoming, which have smaller populations but are disproportionately represented in the Electoral College and thus would be expected to resist its replacement, is unnecessary for the NPVIC’s success.

However, not all proponents of abolishing the Electoral College support the NPVIC. A common argument against the compact is that an accurate national popular vote tally may be harder to obtain than many envision. Systems like ranked choice voting that do not provide an explicit popular vote total may lead to thousands of votes being discounted or stop NPVIC from functioning at all. However, the NPVIC can be amended by states that have already passed it to account for ranked-choice voting systems. Although this may pose a challenge, it’s far from the fatal setback for the NPVIC that some might suggest.

Currently, the NPVIC has been adopted by 17 states, totaling 209 electoral votes, or roughly 77% of the total 270 needed. Unfortunately for proponents of the initiative, the last 61 votes may prove the hardest to accumulate. The proposal is currently pending in the chambers of 10 states: Nevada, Arizona, Michigan, Wisconsin, Kansas, Alaska, Kentucky, Virginia, South Carolina, and North Carolina. If all these states passed the compact, 97 electoral votes would be added, putting the compact well over the 270 threshold. However, in many of these states, the legislation has reached a deadlock for several years, with no action taken due to shifts in partisan control of state legislatures, leading to a lack of support to pass the compact.

In states dominated by Republicans, the likelihood of passing the bill is slim due to the popular vote’s slight partisan lean toward Democrats. This political reality creates a significant obstacle for the NPVIC. However, historical trends indicate growing discontent with the Electoral College across major political parties. This sentiment is especially pronounced among younger generations, who are more inclined to favor electoral reform.

The political appetite for replacing the Electoral College is rising, and the NPVIC is a viable solution that is gaining traction. As awareness of the NPVIC’s benefits spreads, it may garner increasing support from a broader demographic, potentially influencing states to reconsider their positions. With the escalating demand for a more representative electoral system, the NPVIC could play a crucial role in shaping the future of American presidential elections.

Correction (April 22, 2024): This article was revised to reflect Maine’s passage of the NPVIC between the time of writing and publication.

Associate U.S. Editor